The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again

The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again by Robert D. Putnam with Shaylyn Romney Garrett.

The is the third Robert Putnam book that I’ve read. I really enjoyed his best known one, Bowling Alone (2000), in which he argues that civic life is collapsing - that Americans aren't joining, as they once did, the groups and clubs that promote trust and cooperation. This undermines democracy, he says. We are "bowling alone." Since 1980, league bowling has dropped 40 percent, hence, the title. I also read Our Kids (2015), in which he shows that widening income gaps really hurt kids at the lower end of the economic spectrum, often to the point that they have no real chance to succeed in life.

The Upswing takes a very broad look at American history between the late 1800’s and today.The book's thesis is that America's Gilded Age — 1870s through 1890s — shows remarkable similarity to our own. These were the days of the Robber Barons - Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and Cornelius Vanderbilt - who became fabulously wealthy as the gap between rich and poor rapidly widened.

Putnam summarizes the period: "Inequality, political polarization, social dislocation, and cultural narcissism prevailed — all accompanied, as they are now, by unprecedented technological advances, prosperity, and material well-being."

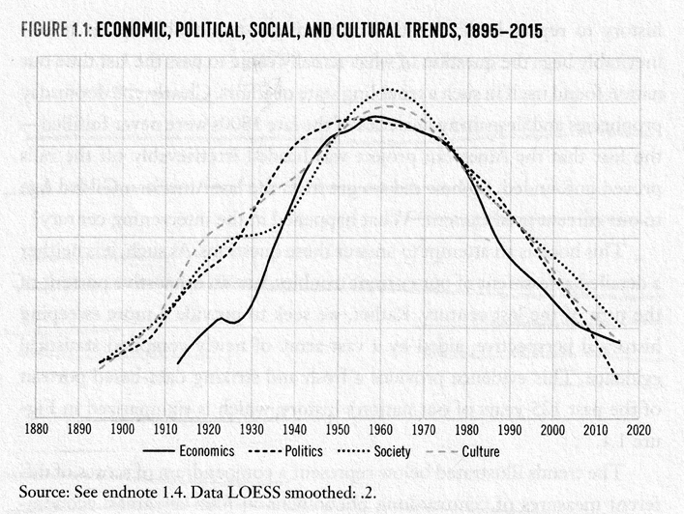

Putnam and Garrett plot a hill-shaped curve to reflect trends from the Gilded Age to the present. They see an "I-we-I" curve cross cutting these issues over the past 125 years.

The “I” piece of the curve refers to times in American history where individual achievement was exalted above any collective endeavors. The “We” part of the curve reflects times when Americans were more concerned about helping out each other than they were about achieving individual success. The top of the curve (the 1960s) represents the lowest gap between rich and poor and times when there was a collective will to work together to improve life.

The authors use a number of factors to plot the curve including health indicators, social spending to help the poor, reduction of the income gap, increased access to education, and lower political polarization.

“I” The left and right sides of the curve reflect years when “I” - the individual - was celebrated . The “I” sides of the curve reflect time frames when public leaders who were shrewd at the game of divide and conquer were successful. That was the case in the late 1800s and early 1900s and in our recent times. The “I“periods also were times of great and widening income and wealth disparity. At the turn of the 20th century, the right to vote was limited to certain people, generally white males. Today, many states are enacting legislation to make voting more difficult.

"We” The “We” part of the curve, which peaked in the middle of the last century, reflects a period when leaders who talked about bringing us together and working for the common good were ascendant. Between 1950 and the 1970s, the income gap shrunk as the economy roared. In the 1960s, Congress passed laws to increase civil rights and voting access for minorities.

As Putman writes, “The story of the American experiment in the twentieth century is one of a long upswing toward increasing solidarity, followed by a steep downturn into increasing individualism. From “I” to “We” and back again to “I.”

Putnam sees the Progressive Era (1896 - 1920) as starting a reform tradition that has since been present in American society. Monopolies were broken up due to violation of federal law. Regulations were enacted to make the water supply, meat packing, and food production safer for consumers. Many labor unions, trade groups, and professional, civic, and religious associations were founded. They improved the lives of individuals and communities. In a capstone to the era, women got the right to vote in 1920.The Progressive Era started the upward trajectory towards a more equal and more communitarian (“We”) society.

The first half of the 20th century saw technological innovation (cars, telephones, radios) as well as solid educational progress as high schools sprung up all across the country, thus providing young people with the skills and tools needed to live productive and successful lives. Between 1900 and 1960, infant mortality dropped sharply as life expectancy increased by 20 years.

The high school graduation rate increased steadily from 1900 to 1965 and then dipped from 78% in 1965 to 68% in 2000. Now it is increasing again.

Income inequality was greatest in the 1920s and for the past ten years, as measured by the share of national income received by the top 1% of people. Today, the top one percent of the population receives over 20% of national income. Between 1960 to 1980, the one percent received about half of what they get today. Since 1975 Income has gone up very little for most Americans, except for those at the top, who have seen huge gains in what they make.

Another measure of the robustness of the economy is intergenerational economic mobility. In 1965, over 90% of children earned more than their parents had. By 2010 only 53% of children earn more than their parent had.

Putnam has no easy answers for why these things happened. He makes a persuasive argument that the Progressive Era reforms changed the course of the country towards being more concerned about all of us than a few of us. This trend was reinforced by FDR’s New Deal and by the social services legislation of the 1960s. He also sees specific policy changes beginning in the 1970s as contributing to the slide towards “I” in our culture. These include spinning our wheels and improving public education for all students; the decline of private sector unions; regressive changes to the tax code; and deregulation of financial institutions. He also cites a shift in national ethos away from “We’re all in this together” to a more libertarian perspective of “Leave me alone.”

Some observers will wonder why inequality is increasing at a time of record federal entitlement and transfer payments to tens of millions of Americans. Putnam points out that most of that money goes to Social Security recipients, not poor families. As the author wryly writes, “The only battle of the War on Poverty that was won was the War on Elder Poverty.”

Politics Political scientists have developed metrics to measure cross-party collaboration in Congress. During the first third of the 20th century, there was very little. Between 1930 and 1980, there was solid bi-partisanship in crafting legislation. The New Deal, World War II, civil rights legislation, all were characterized by relatively bipartisan support. An analysis of presidential inaugural speech showed that Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson (1953 - 1965) gave speeches that stressed shared national values.

By the late 1970s, the shared consensus was shredding. As my two alert readers recall from my summary of Reaganland, the New Right, created in the 1970s, shifted the political focus away from economics to cultural issues - anti-abortion; anti-gay; anti-feminist; pro-traditional family; pro-church. Gerrymandering - creating congressional districts that are safe seats for each party - also has moved us away from working together in Washington. To get reelected - the main goal of politicians - you just have to play to your base. There are almost no moderate Republicans or moderate Democrats in DC. That means that the individual Republican and Democrat members of Congress share little common ground on anything.

One interesting chart in the book shows the number of incidents of party conflict (R’s and D’s) reported in newspapers over time. Between 1925 and 1965, it was relatively peaceful, with an average of about 45 stories. After that, the incidence of stories on political conflict increased dramatically, up to 115 in 2015. That number has probably increased over the past few years not covered in the chart.

The net result of hard-wired political strife is citizen alienation. In April, 2018, a Pew Research Center poll asked if the government was run for “the benefit of all” or for “a few big interests.” The results weren’t surprising - 82% said for the big interests. In 1964, a similar poll had very different results - 64% said the government worked for the benefit of all.

Social solidarity Putnam’s Bowling Alone is about social connectivity in the United States - how people organize to improve things that need to be improved. Alexis DeTocqueville was amazed at how many voluntary associations he found in our country, forums for people to come together to accomplish a task without waiting for the government to jump in. Associations thrived after the Civil War. By 1910, one-third of all American males over nineteen belonged to a civic, religious or fraternal association. While white males were the alphas in society back then, women and Blacks also formed associations that were a vital part of the community.

Many women joined the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the National Congress of Mothers which became the Parents Teachers Association (PTA). Blacks organized the Prince Hall Freemasons as well as local civic groups that work on issues relating to Black empowerment. The percentage of people in associations climbed dramatically between 1900 and 1960 and then began to drop steadily. By 2000, all of the gains in association membership between 1900 and 1960 had disappeared. People were not into joining with others to do things. Today, non-profit organizations have thrived, and tens of millions of Americans belong to them. But being a “member” of a National Public Radio station or the National Rifle Association means contributing money to them. There is no real socialization involved in writing a check.

Religion Americans have a hit-or-miss relationship with organized religion. For most of our history, church attendance was not a priority for most people. The 1950s and early 1960s were the high-water mark for church affiliation, with the drop-off beginning in the late 1960s when many people began to question a lot of things, including the importance of being a member of an organized church. It may be facile to say that the “Do your own thing” hurt churches, but it did. When the choice was between sexual liberation and adhering to conservative church dogma on restricting sex to married couples, more-sex-for-everyone won. More recently, the Catholic Church’s clergy sex scandals really hurt membership.

Starting in the late 1960s, more fundamentalist evangelicalism became attractive to more and more traditional Protestants. In the 1970s, the Christian Right gained strength and became a potent political force. In the 1990s, many people were sick of them all and were choosing ”None” when queried about church affiliation.

Marriage Until 1910, about 65% of the population was married. In 1960, the number increased to 80%. By 2016, only 45% of Americans were married. There are two reasons for this. The first is that a lot of people don't want to get married. They can be in a relationship and have kids without being married without the social stigma that they would have felt 40 or 50 years ago. The other reason for a declining percentage of married people is the high rate of divorce. For the past 50 years or so, self-fulfillment was a top priority for many people; for their parents, staying in the marriage was the main goal. Marriage was a stabilizing and unifying influence at the middle of the last century that may have helped bring us together, but it is unlikely that many people will suddenly decide to get married any time soon.

Culture One of the consistent themes of the book is the tension between individualism and community in our culture. At the beginning of our republic, the yeoman farmer was the typical American, although there was a lot of social activity in the cities that was harnessed to trigger the War for Independence. Later, frontier life set the template for individualism. Social Darwinism, the idea that the cream will rise to the top of society, gave a certain legitimacy to the Robber Barons of the late nineteenth century. After all, if they were so successful, they must be better than the rest of society. They deserved their wealth. That type of thinking - that some people were naturally better than others - inexorably led to the “science” of eugenics which held that other races and ethnics were inferior to the superior whites. That type of thinking opened the door to Jim Crow laws in the South and a contempt for immigrants and “others” who were different from and inferior to the elites. One of eugenics biggest fans was Adolph Hitler.

Over the past hundred years or so, two of the dominant strains in our culture have been the contrasting ideas of “survival of the fittest” (Social Darwinism - individualism) and “the social gospel” (communitarianism) which held that doing good for the most, especially the needy, was the main goal of society. Putnam’s research is based on the incidence of each phrase in all book references over time. (Believe it or not, you can Google phrases as “Ngrams” and come up with a count of words and phrases.)

These Ngram Internet searches show that Social Darwinism dominated the early years of the 20th century, peaking in the 1920s and steadily fading until 1990 when the concept started to regain popularity. The social gospel started to gather momentum around 1910, coincident with the rise of the Progressive Era, and steadily increased in popularity until - you guessed it! - 1965. From then on, the concept declined in popularity. Today, each of those constructs has the same percentage per million words in books. We seem to have a tie here, but the trend lines indicate that survival of the fittest is gaining in popularity today.

Putnam talks about the impact of the 1970s New Right and the 1960s New Left on the parties today. The New Right has been imprinted on the Republican Party - cultural issues like abortion, resistance to gay and transgender people, and being anti-immigrant are the hallmark of Republicans today, along with a healthy dose of “The election was stolen.” Concerning Democrats, there’s not much left of the communitarian spirit of the early New Left. Over time, that group splintered into various factions - the violent, anarchist Weathermen and another faction ideology based on identity politics. To a large extent, the Democratic party today is based on identity politics which is far away from communitarianism which merges identities to accomplish a greater good.

Many Americans today are comfortable with defining a lot of life through their own identity and interests. In 1950, 12% of students agreed with the statement that “I am very important.” By 1990, that number had risen to 80%.

Some Limitations

Robert Putnam is very good at what he does in using data to analyze and explain the ebbs and flows of American history and culture. In this book, he uses a variety of measures to describe the United States over 125 years. By his own admission, two areas where the book falls short are in matters of race and gender. One problem is that, for half of the timeframe that the book covers, women and Blacks were not prominent in the civic and political life of the country. Blacks and women had the right to vote, but their voices were often muted in terms of the development of the nation.

Another problem was that there was relatively little data available about the role of Blacks and women in the evolution of the country between 1890 and 1940 or so.

Race After the Civil War, it seemed that the country would smartly move away from the legacy of slavery and work to provide substantive rights and opportunities to African Americans. However, the deal crafted to settle the election of 1876 put Republican Rutherford B. Hayes in the White House in exchange for giving Democrats the South free rein in clamping down on the rights of freed slaves. That triggered a downward spiral of Black rights that set back the cause of racial equity for decades.

One major point in the book is that between 1910 and 1980 Blacks achieved a lot in terms of improving their lives.

- The gap between life expectancy for whites and Blacks shrunk dramatically.

- Income inequality between Blacks and whites dropped significantly between 1940 and 1980. However, since then there has been little closing of the gap.

- Until 1950, Blacks were closing the gap in the percentage of people owning homes. Although there was some progress between 1960 and 1985, over the next 30 years Blacks lost the gains they had made. By 2017 the percentage of Black home ownership had fallen back to what it was in 1950. Putnam sees redlining and the resistance of some people to sell to minorities as factors here.

- In terms of voting participation, Blacks made huge gains between 1940 and 1970, with the greatest gains between 1952 and 1964, ironically just before the Voting Rights Act passed.

- While white educational achievement was rising between 1940 and 1970, Black educational attainment was rising even faster. One reason behind this was the sharp increase in spending on Black schools in the South between 1940 and 1954 - up 288%- compared to a much lower increase in spending on white schools - up 38%. Ironically, in the 1970s the trend towards school integration leveled off and schools in fact began to become more segregated all over the country.

Putnam characterizes these stalls in progress towards equity as “taking a foot off the gas.” Other things distracted us - the Vietnam War, Watergate, very high inflation and interest rates, and a sagging economy - so we didn’t follow up and provide the additional help needed to realize our goals.

(This is a Bob in the Basement observation. I’ve done a lot of historical and public policy research over the decades. One strong tendency that I’ve seen is to think that passing legislation fixes a problem. The mid-1960s were a bountiful time for enacting civil rights, anti-poverty, and education improvement laws and programs. Unfortunately, once bills were signed, a lot of people took their foot off the gas and moved on to do other things. This left undone the hard work needed to redress the problems referenced in the enacted laws and programs.)

Putnam cites several factors that help explain the success of Blacks in closing various gaps until around 1970.

The Great Migration. Between 1910 and 1970 millions of Blacks moved out of the South and to the North where, despite strong racism, there were greater opportunities.

Public and private initiatives. During the first half of the 20th century, many private foundations funded various programs to help African Americans succeed in life. Many federal programs of the period also benefited Blacks. Programs to provide clean water and safe food, to drain swamps to get rid of mosquitos, and to bring health care to rural regions, greatly benefited Blacks.

The long Civil Rights movement. This is the term to describe the activism of African Americans during the 20th century. The NAACP, the Urban League, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters were each successful in promoting a Black success agenda, as were countless smaller local groups.

Some good news Racism is still An American Dilemma, to reference Gunnar Myrdal’s 1944 seminal reflection on the role of race in the United States. We have huge problems which do not seem to be getting better. One positive trend is the support among white people for racial equality. Putnam synthesizes a lot of survey research over the past 70 years that shows steadily increasing support among whites for equal job access, interracial schools, Blacks being elected to political office, residential choice, and interracial marriage. That’s good news. The bad news is that it’s a lot easier to say “Yes” to a pollster than it is to actually take action to fix problems related to race.

Gender Women have made solid gains over the past hundred years, since earning the franchise in 1920. Putnam notes that women, in contrast to Blacks, are continuing to make steady progress in redressing inequality.

Women historically have been more likely than men to get a high school diploma, probably because for many years men would drop out and go to work. Even today, girls have a slightly higher rate of high school completion than boys. College completion is where we see a big change since 1970. Then college graduates were 50% men and 50% women. Today, 57% of degree recipients are women, and 43% of the graduates are men. This trend also holds for master’s degrees and doctorates.

On a related note, I did a study about ten years ago for an education think tank that looked at male and female MCAS (yearly state assessments) English and math scores. Historically, girls did better in English and boys did better in math. That has changed, at least in Massachusetts. Around 2005, girls started doing better in math than boys, and females continued to get higher scores in English. That may not be good news for males, but it may open up some science, technology, engineering and math opportunities for females.

The percentage of females in the labor force steadily increased over the past century until 1990 when it flattened at around 60%. By 2015, 70% of men (a drop from 90% in 1930) and 57% of women (up from 24% in 1930) were in the labor force.

While women are an integral part of labor, pay gaps remain a problem. The largest modern disparity was around 1970 when women earned 58% of what men did. By 2010, the gap had gotten better, but women still made only 77% of what men did.

Putnam attributes this pay gap to occupational segregation - women have not had access to the better-paying jobs, especially in the service sector. That may change. Since women are more likely to finish high school, and much more likely to complete college and graduate school, down the road more and more females will have opportunities for jobs that require advanced education.

In politics, women began to pick up seats in Congress in 1990 when there were 30 women in federal office. By 2018, there were 130. In terms of voting, as late as 2000, fewer women voted than men. In 2016 female turnout was 4% more than males.

Today Americans generally support equity for women across many dimensions. While some older people have reservations about some feminist goals, younger Americans are fully on board with opening up the country to opportunities for females. There is much left to do, but the future looks good for the ladies.

The Arc of the Twentieth Century

Putnam ends his analysis by reaffirming that the pivot point for the peak of communitarian society was 1965, when “We” was (were?) ascendant. After that, the nation devolved towards the individualistic “I” side of the economic, social and cultural landscape, which is where we are today. He talks about causation - why this happened - but he doesn’t have any pat answers. He tries to find leading indicators among the dozens of variables he considered that would have predicted the arc of the century but he doesn’t find any. He found that economic inequality, rather than leading the way to our “I” society, was the caboose – the result of what happened, not the cause. There is nothing consistent in the politics of the period that explains what happened. The notion of “culture” can be fuzzy, but he can find no cultural canaries that foretold our slide away from the “We” world to our “I” world.

He considers two potential suspects: The Internet and Young People. While Millennials love Twitter and Facebook (as does Boomer ex-President Trump), they and the technology were not the cause of where we are.

Conservatives blame government spending which has gone up inexorably, regardless of who is in the White House, but increasing spending lagged way behind indicators of a return to the individualistic “I” society.

Some people have argued that entrenched economic inequality, with many people being worried about earning a living, caused us to retrench to “I”. But the Depression produced much greater financial stress and that was a time that drove the country towards becoming a “We” society in the 1940’s, 1950s, and 1960s. Putnam also considers and dismisses the impact of immigration, the struggle for gender and racial equity, and globalization as being major drivers of how society changed over the past 60 years.

The 1960s The decade was comprised of two distinct pieces. The first half of the decade were “years of hope and change” while the end of the decade was characterized by “days of rage.” At the beginning of the 1960s, JFK inspired people with his soaring rhetoric and focus on the future. A few years after his assassination, massive student protests, the killings of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, and the creation of the Weathermen and other violent anti-establishment groups changed the civic terrain. As we exited the decade, we began to fight culture wars that are still with us today. Vietnam fractured the country and led to Richard Nixon’s 1968 win. For most of the decade, the economy was booming, but by the mid-1970s, that had changed and people worried about money.

For much of the decade the music was upbeat and bouncy - Beatles tunes, Motown - but by the end of the period even the Beatles were more into isolation and individualism.<em> Eleanor Rigby</em> asked, “All the lonely people/Where do they all come from?”

Starting in 1965 there were major race riots in Los Angeles, Newark and Detroit. We saw the carnage in Vietnam up close and personal via TV. The sexual revolution probably turned off as many people as it exhilarated. And you could make a pretty good argument that the 1960s didn’t end in 1969, but rather with the Watergate scandal of 1974, which tainted much of the country’s view about politics and led to a massive distrust of government.

One of the major ironies of the 1960s was that the move towards “We” spawned myriad progressive movements that “emphasized individualism and individual rights at the expense of widely shared communitarian values... Movements to liberate individuals in many cases had the unintended side effect of elevating selfishness,” according to Putnam. Thus, in a real sense, the “Peace, Love and Rock ‘n’ Roll” of what is probably the most revered decade in my lifetime set us on a course that led to where we are now, with few common values and even having basic disagreements on facts.

The Road Ahead

“... with many a winding turn that leads us to who knows where, who knows where,” to quote a 1969 song by the Hollies. Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett do an excellent job of bookending the course of the past 125 years. There are indeed striking similarities between the Gilded Age of the late 19th century and the Greed Era of today. Even conservatives recognize that income inequality is increasing. Some may find comfort in that, but growing the income and wealth chasms between the haves and the have-nots is not a good foundation for social stability.

It is unsurprising that Robert Putnam looks to the Progressive Era for clues about what to do to get the country back to worrying about all of us - “We” - as opposed to the few of us who are at the top of society today. The pandemic is over, but one of its unintended consequences was the widening of the gap between rich and poor. Working people, especially those in the hospitality industry, have been out of work for a year. Rich folk, with extensive stock market investments, made out like bandits, or robber barons.

Putnam gives brief biographies of four people who made a difference in moving the country from “I” to “We” in the first half of the 20th century. They did make a difference, but they were helped by extraordinary presidential leadership, including Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt. We also had a wrenching Depression and a monstrous World War to bring us together. Given how partisan and digital media driven and gerrymandered politics is today, we probably won’t see that quality of leadership in the White House anytime soon. That means that citizen-led action has to be the foundation for bringing about meaningful change.

That’s a tall order. Theoretically, digital media makes it easiest to organize people, but that may not be the case. Having been at the center of two grass-roots efforts to defeat major developers who wanted to build silly things in the 46 acres of green space in our backyard, I know what’s involved in getting people to show up and do things. Back then, in the mid-1990s, people would answer the phone or the door and you could talk to them. Today, those techniques don't work. You can set up a Facebook page and tweet stuff, but these are passive activities. You miss the chance to make the case personally, which can be very persuasive.

In the last chapter, Robert Putnam makes the key point: fixing what’s wrong with our country involves persistent political activity. You have to win elections. He sees young people as the key to doing this, just as most of the leaders of the Progressive Era were in their thirties. He also sees climate change as a unifying issue for young people. I’m not sure about that. It seems that the blatant income and wealth gaps are more pressing problems, especially if you’re a young person struggling to make a living. But I’m an old guy. What do I know?

Bob's Take

Lots of numbers. This is a sharp, data-centric analysis with lots of graphs and numbers, which Bob in the Basement really likes. There are almost 100 graphs and charts - Nirvana to me! Putnam always uses established data sources to make his points and this book reflected that.

No real solution. While the authors nailed the analysis in terms of making the argument that today’s America has much in common with the nation of 100 years ago, they don’t come up with a to-do list to fix things. That’s not a criticism; it took us decades to get where we are today and it will take many years to get back to a more civil and opportunity-driven society.

We’ve been here before. Many Americans “don’t know much about history,” to quote Sam Cooke’s 1960 hit, What a Wonderful World. This book reminds us that the history of the United States has been really rocky. Many of us born after WWII have been spoiled in that we came of age during unprecedented prosperity and peace (except for Korea and Vietnam). Older Americans have had a pretty easy ride, although people born since 1980 or so have been negatively affected by two major recessions and a declining standard of living for many.

Identity politics could get in the way of coming together. The relatively recent shift among some people to see most everything in terms of identity politics means “an abandonment of a broader cooperative ethic in the public square,” to quote Putnam. He sees the results of embracing identity politics leading to a “fractured notion of citizenship - based less on broad commonality and more on claiming rights and privileges associated with a narrowed sense of group identity.” That does not augur well for creating a <em>Kumbaya</em> consensus around the need to move back towards a more communitarian country that brings back more of the “We” and moves away from the “I”.

Some reviewers on the progressive side of the ideological spectrum were not happy with the book. They criticized Putnam for not doing more with gender and race issues (which take up a full 25% of the text) and for obliquely criticizing identity politics. Having read several of his books, I know that Putnam is fairly neutral in his analyses so I didn’t buy the criticism.

Personal correspondence. After I read Bowling Alone, one of the best book titles ever, I tricked the good professor into responding to my stalking emails. We went back and forth a bit. Some of the research I was doing had a tenuous relationship to some of his more cogent observations.